Last month I gave a presentation at The Wilson Center about the publication of my new book, Hot, Hungry Planet: The Fight to Stop a Global Food Crisis in the Face of Climate Change (St. Martin’s Press). I write about how global agriculture is ready for sustainable solutions. The Pulitzer Center provided support for my reporting in India, where I found that climate change is altering agriculture across a variety of societies. I observed how people are working together to develop climate smart villages and asked: What does this mean for their food security, especially for the world’s most vulnerable people?

Last month I gave a presentation at The Wilson Center about the publication of my new book, Hot, Hungry Planet: The Fight to Stop a Global Food Crisis in the Face of Climate Change (St. Martin’s Press). I write about how global agriculture is ready for sustainable solutions. The Pulitzer Center provided support for my reporting in India, where I found that climate change is altering agriculture across a variety of societies. I observed how people are working together to develop climate smart villages and asked: What does this mean for their food security, especially for the world’s most vulnerable people?

The Pulitzer Center covered my book launch at the Wilson Center, and this is how their report begins:

A confluence of environmental, social, and economic factors are leading to major food shortages around the world, especially in poorer countries. By drawing upon her reporting and research on the environment, sustainability, and agriculture, Pulitzer Center grantee Lisa Palmer looks at the factors threatening global food security in her new book Hot, Hungry Planet: The Fight to Stop a Global Food Crisis in the Face of Climate Change.

Palmer launched her book at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., where she was previously a public policy scholar. The Wilson Center, a U.S. Presidential Memorial, serves as a policy forum on global issues and supports researchers and discourse. At the launch, the Wilson Center invited Palmer and a group of experts to comment on Hot, Hungry Planet and what challenges and opportunities are currently available to stem food shortages. Panelists included: Channing Arndt, senior research fellow at International Food Policy Research Institute; Roger-Mark DeSouza, Director of Population, Environmental Security, and Resilience at the Wilson Center; and Nabeeha Kazi, president and CEO of Humanitas Global.

In Hot, Hungry Planet, Palmer explores the future of food security through seven case studies located in six regions around the world: India, sub-Saharan Africa, the United States, Latin America, the Middle East, and Indonesia. Through these examples, Palmer looks at how the global population boom (expected to reach 9.7 billion people by 2050), climate change, and the widening socioeconomic divide will make feeding the world challenging.

To read the complete story on the Pulitzer Center website, please follow this link.

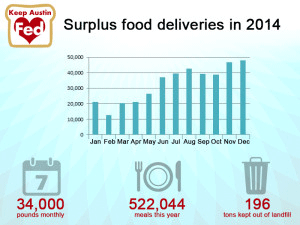

That’s Russell Cavin of Keep Austin Fed, a Texas not-for-profit that rescues nutritious, edible food, and delivers it to local Austin charities. In a county where almost one in five people do not know where their next meal is coming from, Cavin says food rescue makes sense. The food comes from supermarkets and restaurants, which often toss perfectly good fare that looks less than perfect – like a pre-made sandwich with wilted lettuce.

That’s Russell Cavin of Keep Austin Fed, a Texas not-for-profit that rescues nutritious, edible food, and delivers it to local Austin charities. In a county where almost one in five people do not know where their next meal is coming from, Cavin says food rescue makes sense. The food comes from supermarkets and restaurants, which often toss perfectly good fare that looks less than perfect – like a pre-made sandwich with wilted lettuce.