Fishing gear stands ready next to the day’s catch on the shore of Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu.Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest fresh water body and the world’s second largest lake, is no longer fresh.The lake is choking with pollution from industrial and agricultural wastes, as well as raw sewage from Kisumu, Kenya’s third largest city of just under 400,000 residents. Its problems are compounded by illegal fishing, catching of juvenile fish, and infestation by the invasive water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes). And there’s also the carnivorous Nile perch (Lates niloticus), an introduced behemoth of a fish that can grow to 200 kilograms (440 pounds) and has already wiped out nearly half of the 500-plus endemic species of Victoria cichlids — colorful fishes that once thrived within the lake basin. “This lake is in a very sorry state,” Moris Okulo, a trained ecologist who has worked as a guide at the lake’s Dunga beach in Kisumu for the past 20 years, told mongabay.com.”Everything about the lake is wrong. Fishermen are using wrong fishing gears, but nobody arrests them. Industries are discharging waste into the lake, but no action is being taken. Some people have built structures including latrines inside the lake with the knowledge of law enforcing personnel, but nobody is even talking about it,” he lamented. Fishing gear stands ready next to the day’s catch on the shore of Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu.Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest fresh water body and the world’s second largest lake, is no longer fresh.The lake is choking with pollution from industrial and agricultural wastes, as well as raw sewage from Kisumu, Kenya’s third largest city of just under 400,000 residents. Its problems are compounded by illegal fishing, catching of juvenile fish, and infestation by the invasive water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes). And there’s also the carnivorous Nile perch (Lates niloticus), an introduced behemoth of a fish that can grow to 200 kilograms (440 pounds) and has already wiped out nearly half of the 500-plus endemic species of Victoria cichlids — colorful fishes that once thrived within the lake basin. “This lake is in a very sorry state,” Moris Okulo, a trained ecologist who has worked as a guide at the lake’s Dunga beach in Kisumu for the past 20 years, told mongabay.com.”Everything about the lake is wrong. Fishermen are using wrong fishing gears, but nobody arrests them. Industries are discharging waste into the lake, but no action is being taken. Some people have built structures including latrines inside the lake with the knowledge of law enforcing personnel, but nobody is even talking about it,” he lamented.

|

Moris Okulo, an ecologist who works as a guide at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, displays mature tilapia from Lake Victoria. He says many fish species have disappeared from the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Moris Okulo, an ecologist who works as a guide at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, displays mature tilapia from Lake Victoria. He says many fish species have disappeared from the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. |

The lake covers 68,800 square kilometers (26,500 square miles) and has 6 percent of its surface area in Kenya, 43 percent in Uganda, and 51 percent in Tanzania, according to the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization (LVFO), an intergovernmental fisheries management institution. For all its problems, Lake Victoria is believed to be the most productive freshwater fishery in Africa. Each year it yields more than 800,000 metric tons of fish with a beach value of up to $400 million and export earnings of $250 million, according to the LVFO. Lake Victoria fisheries support the livelihoods of nearly 2 million people and help feed nearly 22 million people in the region, the organization’s website states. Foul water All that, as well as the lake’s ecological integrity is at stake. Authorities in the three countries are fully aware of the lake situation, with the Kenya National Cleaner Production Centre (KNCPC) pointing out that 88 industries operating around the lake collectively dump seven tons of industrial waste into the lake every year. Yet none of the three countries prosecute offenders.  Fishermen unload their catch at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Instead, KNCPC encourages businesses in the three countries to voluntarily adopt waste-prevention technologies, promising eventually to set mandatory requirements. The KNCPC and its regional partners also reward manufacturing companies they deem to have cut environmental pollution through a $3.5 million World-Bank-funded program to reduce pollution to the lake basin. Within the reward scheme, Kenya’s Nzoia Sugar Company Ltd won the 2014 solid waste management award, despite the fact that its farmers use chemical fertilizers that end up in the Nzoia River, which feeds into the lake. “The truth is that all these industries located near the lake have a hidden agenda to release effluents into the lake. If hard pressed, they will talk about measures put in place or being put in place to purify the water before it is released into the lake,” Gaster Kiyingi, a Ugandan communications consultant and activist who has worked for environmental groups in the region for the past decade, told mongabay.com. Kiyingi observed that because of the high level of corruption in many African countries, illegal activities that harm the lake often go unpunished. Fishermen unload their catch at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Instead, KNCPC encourages businesses in the three countries to voluntarily adopt waste-prevention technologies, promising eventually to set mandatory requirements. The KNCPC and its regional partners also reward manufacturing companies they deem to have cut environmental pollution through a $3.5 million World-Bank-funded program to reduce pollution to the lake basin. Within the reward scheme, Kenya’s Nzoia Sugar Company Ltd won the 2014 solid waste management award, despite the fact that its farmers use chemical fertilizers that end up in the Nzoia River, which feeds into the lake. “The truth is that all these industries located near the lake have a hidden agenda to release effluents into the lake. If hard pressed, they will talk about measures put in place or being put in place to purify the water before it is released into the lake,” Gaster Kiyingi, a Ugandan communications consultant and activist who has worked for environmental groups in the region for the past decade, told mongabay.com. Kiyingi observed that because of the high level of corruption in many African countries, illegal activities that harm the lake often go unpunished.  Fish sit atop a mosquito net. Fishermen often use the nets, which may be treated with insecticides, but the tiny mesh entraps fish of all sizes, including juveniles needed to replenish fish stocks. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Sewage is another major source of pollution. On the Kenyan side, four major towns of Kisumu, Bondo, Homa Bay, and Migori that border the lake have malfunctioning sewage treatment plants or none at all. Just 10 percent of households in Kisumu city are connected to the sewer system, according to an environmental and social impact report for a project to upgrade portions of the system. “Consequently, raw sewage is often discharged into the lake directly from unconnected sources through open drains or partially treated sewage from the treatment systems,” the report states. Open sewers running from all corners of the city and deliberately directed into the lake are evident on the lake shore. Fish sit atop a mosquito net. Fishermen often use the nets, which may be treated with insecticides, but the tiny mesh entraps fish of all sizes, including juveniles needed to replenish fish stocks. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Sewage is another major source of pollution. On the Kenyan side, four major towns of Kisumu, Bondo, Homa Bay, and Migori that border the lake have malfunctioning sewage treatment plants or none at all. Just 10 percent of households in Kisumu city are connected to the sewer system, according to an environmental and social impact report for a project to upgrade portions of the system. “Consequently, raw sewage is often discharged into the lake directly from unconnected sources through open drains or partially treated sewage from the treatment systems,” the report states. Open sewers running from all corners of the city and deliberately directed into the lake are evident on the lake shore.  An open drainage sends untreated sewage from Kisumu, Kenya’s third largest city of just under 400,000 residents, directly into Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “The designers of the city did not consider the new settlements that are still coming up in Kisumu. As a result, the sewage system that was put in place cannot cope with the current pressure,” Antony Saisi, Kisumu County Director of Environment at the Kenyan government’s National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), told mongabay.com. Fortunately, in the town of Homa Bay a sewage treatment plant is now being constructed right by the shore of Lake Victoria with financing from the World Bank. Until it is completed, raw sewage from the broader Homa Bay County, with a population of 960,000, will continue to make its way to the lake. At Dunga Beach in Kisumu city, public restrooms serving over 5,000 people who visit the beach every day hold pit latrines suspended right over the lake. An open drainage sends untreated sewage from Kisumu, Kenya’s third largest city of just under 400,000 residents, directly into Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “The designers of the city did not consider the new settlements that are still coming up in Kisumu. As a result, the sewage system that was put in place cannot cope with the current pressure,” Antony Saisi, Kisumu County Director of Environment at the Kenyan government’s National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), told mongabay.com. Fortunately, in the town of Homa Bay a sewage treatment plant is now being constructed right by the shore of Lake Victoria with financing from the World Bank. Until it is completed, raw sewage from the broader Homa Bay County, with a population of 960,000, will continue to make its way to the lake. At Dunga Beach in Kisumu city, public restrooms serving over 5,000 people who visit the beach every day hold pit latrines suspended right over the lake.  A pit latrine at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, empties directly into Lake Victoria. It is one of numerous streams of untreated human waste entering the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The same thing happens at the city’s Lwang’ni Beach. The beach sits about 100 meters off Oginga Odinga Street, and vehicles drive right down into the lake to be washed, spilling fuel directly into the water. The beach’s name, lwang’ni, means “housefly” in the local Dholuo language, perhaps as a nod to the filthy status of the surroundings. A pit latrine at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, empties directly into Lake Victoria. It is one of numerous streams of untreated human waste entering the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The same thing happens at the city’s Lwang’ni Beach. The beach sits about 100 meters off Oginga Odinga Street, and vehicles drive right down into the lake to be washed, spilling fuel directly into the water. The beach’s name, lwang’ni, means “housefly” in the local Dholuo language, perhaps as a nod to the filthy status of the surroundings.  Trucks and a bus are washed right in Lake Victoria at Lwang’ni beach in Kisumu, Kenya. The business is illegal but it goes on with the knowledge of environmental authorities. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “We have not been able to tame washing of vehicles inside the lake because of lack of political support,” said Saisi of NEMA. “We are dealing with hooligans who are politically connected,” he said. Behind the beachside facilities, the flies celebrate upon open sewer trenches discharging directly into Lake Victoria. Meanwhile, food kiosks erected on platforms extending into the waters of the lake serve thousands of visitors every day. The kiosks have no solid waste collection services, which means napkins, fish bones, bottle caps, and plastic bags also end up into the lake. Trucks and a bus are washed right in Lake Victoria at Lwang’ni beach in Kisumu, Kenya. The business is illegal but it goes on with the knowledge of environmental authorities. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “We have not been able to tame washing of vehicles inside the lake because of lack of political support,” said Saisi of NEMA. “We are dealing with hooligans who are politically connected,” he said. Behind the beachside facilities, the flies celebrate upon open sewer trenches discharging directly into Lake Victoria. Meanwhile, food kiosks erected on platforms extending into the waters of the lake serve thousands of visitors every day. The kiosks have no solid waste collection services, which means napkins, fish bones, bottle caps, and plastic bags also end up into the lake.  Students buy a snack of juvenile Nile perch from a kiosk at Dunga beach in Kisumu, Kenya. An estimated 5,000 people visit the beach daily to eat fish and view the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “The situation is not any different here in Kampala,” located a four-hour drive to the west of Kisumu, said Kiyingi. “The lake is on its knees, and if the situation is not reversed, it will literally die.” A fisherman at Dunga beach, Jerald Otieno, told mongabay.com that he and his fellow fishermen often stay in their boats out on the lake for more than 15 hours at a stretch. “We carry food with us when we go fishing, and when it comes to answering calls of nature, we have no choice but relieve ourselves in the lake,” he said. Students buy a snack of juvenile Nile perch from a kiosk at Dunga beach in Kisumu, Kenya. An estimated 5,000 people visit the beach daily to eat fish and view the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “The situation is not any different here in Kampala,” located a four-hour drive to the west of Kisumu, said Kiyingi. “The lake is on its knees, and if the situation is not reversed, it will literally die.” A fisherman at Dunga beach, Jerald Otieno, told mongabay.com that he and his fellow fishermen often stay in their boats out on the lake for more than 15 hours at a stretch. “We carry food with us when we go fishing, and when it comes to answering calls of nature, we have no choice but relieve ourselves in the lake,” he said.  Fishing vessels ply Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. As a result of all the human waste pouring into the lake, a recent study revealed traces of estrogenic endocrine disruptors in the lake. All water samples analyzed from nine sites in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania tested positive for several estrogenic compounds that can be released from human urine and fecal matter. In a documentary, Paul Mbuthia, an associate professor of veterinary pathology at the University of Nairobi who co-authored the study, says that high concentrations of such hormonal chemicals can cause abnormalities in animals, including humans. “They interfere with normal organ system. With high quantities of estrone, chances of getting animals becoming more feminine are very possible,” he said. “Others can cause tumors in the system.” The lake provides water for domestic and other uses for millions of people around it, notably in Kisumu in Kenya, the capital city of Kampala in Uganda, and the town of Mwanza in Tanzania. Fishing vessels ply Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. As a result of all the human waste pouring into the lake, a recent study revealed traces of estrogenic endocrine disruptors in the lake. All water samples analyzed from nine sites in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania tested positive for several estrogenic compounds that can be released from human urine and fecal matter. In a documentary, Paul Mbuthia, an associate professor of veterinary pathology at the University of Nairobi who co-authored the study, says that high concentrations of such hormonal chemicals can cause abnormalities in animals, including humans. “They interfere with normal organ system. With high quantities of estrone, chances of getting animals becoming more feminine are very possible,” he said. “Others can cause tumors in the system.” The lake provides water for domestic and other uses for millions of people around it, notably in Kisumu in Kenya, the capital city of Kampala in Uganda, and the town of Mwanza in Tanzania.  Fishermen at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, prepare for a night of fishing. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Weak government To salvage the situation, a regional body known as the Lake Victoria Environmental Management Programmeis working with support from the World Bank, the Global Environment Facility, the government of Sweden, and the East African Community partner states to reduce environmental stressors throughout the lake’s drainage basin and to enhance the basin’s ecological integrity. The project, running between 2009 and 2017 at a cost of $254 million, is taking aim at a variety of problems, including deteriorating lake water quality due to sedimentation, pollution, and eutrophication; declining lake levels; the resurgence of water hyacinth and other invasive weeds; and over-exploited natural resources throughout the lake basin. Fishermen at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, prepare for a night of fishing. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Weak government To salvage the situation, a regional body known as the Lake Victoria Environmental Management Programmeis working with support from the World Bank, the Global Environment Facility, the government of Sweden, and the East African Community partner states to reduce environmental stressors throughout the lake’s drainage basin and to enhance the basin’s ecological integrity. The project, running between 2009 and 2017 at a cost of $254 million, is taking aim at a variety of problems, including deteriorating lake water quality due to sedimentation, pollution, and eutrophication; declining lake levels; the resurgence of water hyacinth and other invasive weeds; and over-exploited natural resources throughout the lake basin.  A thicket of invasive water hyacinth clogs a Ugandan shore of Lake Victoria. The weed has colonized huge swathes of the lake. Photo credit: sarahemcc. However, despite this and other efforts in place, many observers contend that the main solution lies in catalyzing political will. Alice Alaso, a Ugandan lawmaker and member of the parliament’s Committee on Natural Resources, told New Vision, a Uganda national newspaper, that lax law enforcement and a lack of political will is choking the lake. “The only solution to the problem of polluting Lake Victoria is enforcement of the law. We do not need another law,” she said. “We do not need additional money to save the lake. All we need is the political will.” “Many things are happening on this lake, but given limited support from the government, there is nothing we can do about it,” Remjus Ojijo, a maritime police officer in Kisumu told Mongabay.com. The officer points to Winam Gulf, an extension of northeastern Lake Victoria into western Kenya, as an example. The gulf is the breeding ground for nearly all the fishes in the lake, and fishing is prohibited there. “But every day, we helplessly watch people cross with boats in these areas, but we cannot go after them because the only two police patrol boats, which were purchased 30 years ago, grounded some four years ago,” he told mongabay.com. A thicket of invasive water hyacinth clogs a Ugandan shore of Lake Victoria. The weed has colonized huge swathes of the lake. Photo credit: sarahemcc. However, despite this and other efforts in place, many observers contend that the main solution lies in catalyzing political will. Alice Alaso, a Ugandan lawmaker and member of the parliament’s Committee on Natural Resources, told New Vision, a Uganda national newspaper, that lax law enforcement and a lack of political will is choking the lake. “The only solution to the problem of polluting Lake Victoria is enforcement of the law. We do not need another law,” she said. “We do not need additional money to save the lake. All we need is the political will.” “Many things are happening on this lake, but given limited support from the government, there is nothing we can do about it,” Remjus Ojijo, a maritime police officer in Kisumu told Mongabay.com. The officer points to Winam Gulf, an extension of northeastern Lake Victoria into western Kenya, as an example. The gulf is the breeding ground for nearly all the fishes in the lake, and fishing is prohibited there. “But every day, we helplessly watch people cross with boats in these areas, but we cannot go after them because the only two police patrol boats, which were purchased 30 years ago, grounded some four years ago,” he told mongabay.com.  Grounded police patrol boats in Kisumu, Kenya. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The two boats, the MV Utumishi and MV Chui, lie idle by the lake. “For four years now, we have not been able to patrol the lake as required. And if we must do it, then we have to hire boats using our money which cannot be refunded by the government,” he said. The toll on fish Evidence of fishing from the breeding grounds can be seen at the beaches, where fishermen dock with big catches of juvenile fish. Observers note that some of the fish caught also seem to be shrinking, indications of overfishing and poor water quality. “Some 15 years ago, fishermen used to come with huge fishes. I used to see Nile perch weighing up to 145 kilograms [320 pounds]. But the biggest I have seen this year was 69 kilograms [152 pounds],” said Okulo, the ecologist. Grounded police patrol boats in Kisumu, Kenya. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The two boats, the MV Utumishi and MV Chui, lie idle by the lake. “For four years now, we have not been able to patrol the lake as required. And if we must do it, then we have to hire boats using our money which cannot be refunded by the government,” he said. The toll on fish Evidence of fishing from the breeding grounds can be seen at the beaches, where fishermen dock with big catches of juvenile fish. Observers note that some of the fish caught also seem to be shrinking, indications of overfishing and poor water quality. “Some 15 years ago, fishermen used to come with huge fishes. I used to see Nile perch weighing up to 145 kilograms [320 pounds]. But the biggest I have seen this year was 69 kilograms [152 pounds],” said Okulo, the ecologist.  A blessing or a disaster? Moris Okulo, an ecologist and lake guide, displays a Nile perch weighing 64 pounds. Carnivorous and fast-growing, Nile perch were introduced to Lake Victoria decades ago as a food source, but they quickly wiped out many native fish species. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. On a recent day, the biggest Nile perch caught weighed just 29 kilograms (64 pounds). The rest were much smaller, some weighing just a few grams. Even the Nile perch, which has been a key disruptor of Lake Victoria’s native ecology, is now at the mercy of hungry fishermen. In a presentation during a recent symposium in Entebbe, Uganda, Mbuthia pointed out that some of the fish samples his team collected for their study on estrogen levels in the lake had gross abnormalities, such as missing tails or fins, missing eyes, deformed bodies, or abnormal body color, which raises a new concern about the health of the fish in the lake. A blessing or a disaster? Moris Okulo, an ecologist and lake guide, displays a Nile perch weighing 64 pounds. Carnivorous and fast-growing, Nile perch were introduced to Lake Victoria decades ago as a food source, but they quickly wiped out many native fish species. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. On a recent day, the biggest Nile perch caught weighed just 29 kilograms (64 pounds). The rest were much smaller, some weighing just a few grams. Even the Nile perch, which has been a key disruptor of Lake Victoria’s native ecology, is now at the mercy of hungry fishermen. In a presentation during a recent symposium in Entebbe, Uganda, Mbuthia pointed out that some of the fish samples his team collected for their study on estrogen levels in the lake had gross abnormalities, such as missing tails or fins, missing eyes, deformed bodies, or abnormal body color, which raises a new concern about the health of the fish in the lake.  Fishing boats rest on the shore of Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Ojijo, the maritime police officer, said that many people have recently been arrested for poisoning fish with various chemicals before picking and selling the carcasses. Other fishermen use inappropriate fishing gear that ends up trapping all sizes of fish, including the very young ones essential for replenishing the fish stock. Some of them even opt for tiny-meshed mosquito nets, which have raised additional concerns about leaching insecticides into the water. Fishing boats rest on the shore of Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Ojijo, the maritime police officer, said that many people have recently been arrested for poisoning fish with various chemicals before picking and selling the carcasses. Other fishermen use inappropriate fishing gear that ends up trapping all sizes of fish, including the very young ones essential for replenishing the fish stock. Some of them even opt for tiny-meshed mosquito nets, which have raised additional concerns about leaching insecticides into the water.  Fishermen on Lake Victoria use inappropriate fishing gear that indiscriminately captures even very young fish, as seen in this photo. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The ecological health of the lake is further compromised by the water hyacinth, an invasive plant that has densely colonized huge swathes of the lake, choking out native aquatic plants and limiting oxygen supplies in the water. The water hyacinth thrives because of the soil and nutrients that flush into the lake whenever it rains. “In many cases, the soil erosion happens because people have cut down trees, and more people are cultivating very close to the lakes and rivers, contrary to regulations to protect wetlands, rivers and lakes,” said Kiyingi, the Ugandan activist. In Kenya, for example, the law requires that land near river banks, lake shores, and sea shores be used sustainably and asserts that special measures to prevent soil erosion, siltation, and water pollution are necessary. And NEMA laws require that new structures be built at least 30 meters from the shore. However, Bridgit Akoth, who owns a food kiosk that extends right into the lake at Dunga beach, told mongabay.com that she need only part with a few shillings to bribe law enforcers to let her go on with her business. “Most of these laws just exist on paper. They are rarely put into force,” said Kiyingi. “And now we have a price to pay, a price of losing the biggest fresh water lake in Africa.” Citations: Fishermen on Lake Victoria use inappropriate fishing gear that indiscriminately captures even very young fish, as seen in this photo. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The ecological health of the lake is further compromised by the water hyacinth, an invasive plant that has densely colonized huge swathes of the lake, choking out native aquatic plants and limiting oxygen supplies in the water. The water hyacinth thrives because of the soil and nutrients that flush into the lake whenever it rains. “In many cases, the soil erosion happens because people have cut down trees, and more people are cultivating very close to the lakes and rivers, contrary to regulations to protect wetlands, rivers and lakes,” said Kiyingi, the Ugandan activist. In Kenya, for example, the law requires that land near river banks, lake shores, and sea shores be used sustainably and asserts that special measures to prevent soil erosion, siltation, and water pollution are necessary. And NEMA laws require that new structures be built at least 30 meters from the shore. However, Bridgit Akoth, who owns a food kiosk that extends right into the lake at Dunga beach, told mongabay.com that she need only part with a few shillings to bribe law enforcers to let her go on with her business. “Most of these laws just exist on paper. They are rarely put into force,” said Kiyingi. “And now we have a price to pay, a price of losing the biggest fresh water lake in Africa.” Citations:

A woman prepares fish at busy Dunga Beach. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. A woman prepares fish at busy Dunga Beach. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu.

| <name=”publish”>This article was produced under the Mongabay Reporting Network and can be re-published on your web site or blog or in your magazine, newsletter, or newspaper under these terms. |

<img src=”http://www.google-analytics.com/collect?v=1&tid=UA-12973256-1&cid=grn&t=event&ea=open&cs=news&cm=gfrn&cn=/2015/0602-esipisu-lake-victoria-polluted-overfished.html”

Original source: http://news.mongabay.com/2015/0602-esipisu-lake-victoria-polluted-overfished.html \ Copyright mongabay 1999-2014 |

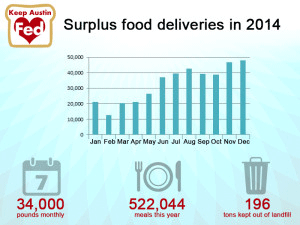

That’s Russell Cavin of Keep Austin Fed, a Texas not-for-profit that rescues nutritious, edible food, and delivers it to local Austin charities. In a county where almost one in five people do not know where their next meal is coming from, Cavin says food rescue makes sense. The food comes from supermarkets and restaurants, which often toss perfectly good fare that looks less than perfect – like a pre-made sandwich with wilted lettuce.

That’s Russell Cavin of Keep Austin Fed, a Texas not-for-profit that rescues nutritious, edible food, and delivers it to local Austin charities. In a county where almost one in five people do not know where their next meal is coming from, Cavin says food rescue makes sense. The food comes from supermarkets and restaurants, which often toss perfectly good fare that looks less than perfect – like a pre-made sandwich with wilted lettuce.

Fishing gear stands ready next to the day’s catch on the shore of Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu.

Fishing gear stands ready next to the day’s catch on the shore of Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Moris Okulo, an ecologist who works as a guide at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, displays mature tilapia from Lake Victoria. He says many fish species have disappeared from the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu.

Moris Okulo, an ecologist who works as a guide at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, displays mature tilapia from Lake Victoria. He says many fish species have disappeared from the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Fish sit atop a mosquito net. Fishermen often use the nets, which may be treated with insecticides, but the tiny mesh entraps fish of all sizes, including juveniles needed to replenish fish stocks. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Sewage is another major source of pollution. On the Kenyan side, four major towns of Kisumu, Bondo, Homa Bay, and Migori that border the lake have malfunctioning sewage treatment plants or none at all. Just 10 percent of households in Kisumu city are connected to the sewer system, according to an environmental and social impact report for a project to upgrade portions of the system. “Consequently, raw sewage is often discharged into the lake directly from unconnected sources through open drains or partially treated sewage from the treatment systems,” the report states. Open sewers running from all corners of the city and deliberately directed into the lake are evident on the lake shore.

Fish sit atop a mosquito net. Fishermen often use the nets, which may be treated with insecticides, but the tiny mesh entraps fish of all sizes, including juveniles needed to replenish fish stocks. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Sewage is another major source of pollution. On the Kenyan side, four major towns of Kisumu, Bondo, Homa Bay, and Migori that border the lake have malfunctioning sewage treatment plants or none at all. Just 10 percent of households in Kisumu city are connected to the sewer system, according to an environmental and social impact report for a project to upgrade portions of the system. “Consequently, raw sewage is often discharged into the lake directly from unconnected sources through open drains or partially treated sewage from the treatment systems,” the report states. Open sewers running from all corners of the city and deliberately directed into the lake are evident on the lake shore.  An open drainage sends untreated sewage from Kisumu, Kenya’s third largest city of just under 400,000 residents, directly into Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “The designers of the city did not consider the new settlements that are still coming up in Kisumu. As a result, the sewage system that was put in place cannot cope with the current pressure,” Antony Saisi, Kisumu County Director of Environment at the Kenyan government’s National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), told mongabay.com. Fortunately, in the town of Homa Bay a sewage treatment plant is now being constructed right by the shore of Lake Victoria with financing from the World Bank. Until it is completed, raw sewage from the broader Homa Bay County, with a population of 960,000, will continue to make its way to the lake. At Dunga Beach in Kisumu city, public restrooms serving over 5,000 people who visit the beach every day hold pit latrines suspended right over the lake.

An open drainage sends untreated sewage from Kisumu, Kenya’s third largest city of just under 400,000 residents, directly into Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “The designers of the city did not consider the new settlements that are still coming up in Kisumu. As a result, the sewage system that was put in place cannot cope with the current pressure,” Antony Saisi, Kisumu County Director of Environment at the Kenyan government’s National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), told mongabay.com. Fortunately, in the town of Homa Bay a sewage treatment plant is now being constructed right by the shore of Lake Victoria with financing from the World Bank. Until it is completed, raw sewage from the broader Homa Bay County, with a population of 960,000, will continue to make its way to the lake. At Dunga Beach in Kisumu city, public restrooms serving over 5,000 people who visit the beach every day hold pit latrines suspended right over the lake.  A pit latrine at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, empties directly into Lake Victoria. It is one of numerous streams of untreated human waste entering the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The same thing happens at the city’s Lwang’ni Beach. The beach sits about 100 meters off Oginga Odinga Street, and vehicles drive right down into the lake to be washed, spilling fuel directly into the water. The beach’s name, lwang’ni, means “housefly” in the local Dholuo language, perhaps as a nod to the filthy status of the surroundings.

A pit latrine at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, empties directly into Lake Victoria. It is one of numerous streams of untreated human waste entering the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The same thing happens at the city’s Lwang’ni Beach. The beach sits about 100 meters off Oginga Odinga Street, and vehicles drive right down into the lake to be washed, spilling fuel directly into the water. The beach’s name, lwang’ni, means “housefly” in the local Dholuo language, perhaps as a nod to the filthy status of the surroundings.  Trucks and a bus are washed right in Lake Victoria at Lwang’ni beach in Kisumu, Kenya. The business is illegal but it goes on with the knowledge of environmental authorities. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “We have not been able to tame washing of vehicles inside the lake because of lack of political support,” said Saisi of NEMA. “We are dealing with hooligans who are politically connected,” he said. Behind the beachside facilities, the flies celebrate upon open sewer trenches discharging directly into Lake Victoria. Meanwhile, food kiosks erected on platforms extending into the waters of the lake serve thousands of visitors every day. The kiosks have no solid waste collection services, which means napkins, fish bones, bottle caps, and plastic bags also end up into the lake.

Trucks and a bus are washed right in Lake Victoria at Lwang’ni beach in Kisumu, Kenya. The business is illegal but it goes on with the knowledge of environmental authorities. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “We have not been able to tame washing of vehicles inside the lake because of lack of political support,” said Saisi of NEMA. “We are dealing with hooligans who are politically connected,” he said. Behind the beachside facilities, the flies celebrate upon open sewer trenches discharging directly into Lake Victoria. Meanwhile, food kiosks erected on platforms extending into the waters of the lake serve thousands of visitors every day. The kiosks have no solid waste collection services, which means napkins, fish bones, bottle caps, and plastic bags also end up into the lake.  Students buy a snack of juvenile Nile perch from a kiosk at Dunga beach in Kisumu, Kenya. An estimated 5,000 people visit the beach daily to eat fish and view the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “The situation is not any different here in Kampala,” located a four-hour drive to the west of Kisumu, said Kiyingi. “The lake is on its knees, and if the situation is not reversed, it will literally die.” A fisherman at Dunga beach, Jerald Otieno, told mongabay.com that he and his fellow fishermen often stay in their boats out on the lake for more than 15 hours at a stretch. “We carry food with us when we go fishing, and when it comes to answering calls of nature, we have no choice but relieve ourselves in the lake,” he said.

Students buy a snack of juvenile Nile perch from a kiosk at Dunga beach in Kisumu, Kenya. An estimated 5,000 people visit the beach daily to eat fish and view the lake. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. “The situation is not any different here in Kampala,” located a four-hour drive to the west of Kisumu, said Kiyingi. “The lake is on its knees, and if the situation is not reversed, it will literally die.” A fisherman at Dunga beach, Jerald Otieno, told mongabay.com that he and his fellow fishermen often stay in their boats out on the lake for more than 15 hours at a stretch. “We carry food with us when we go fishing, and when it comes to answering calls of nature, we have no choice but relieve ourselves in the lake,” he said.  Fishing vessels ply Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. As a result of all the human waste pouring into the lake,

Fishing vessels ply Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. As a result of all the human waste pouring into the lake,  Fishermen at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, prepare for a night of fishing. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Weak government To salvage the situation, a regional body known as the

Fishermen at Dunga Beach in Kisumu, Kenya, prepare for a night of fishing. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Weak government To salvage the situation, a regional body known as the  A thicket of invasive water hyacinth clogs a Ugandan shore of Lake Victoria. The weed has colonized huge swathes of the lake. Photo credit:

A thicket of invasive water hyacinth clogs a Ugandan shore of Lake Victoria. The weed has colonized huge swathes of the lake. Photo credit:  Grounded police patrol boats in Kisumu, Kenya. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The two boats, the MV Utumishi and MV Chui, lie idle by the lake. “For four years now, we have not been able to patrol the lake as required. And if we must do it, then we have to hire boats using our money which cannot be refunded by the government,” he said. The toll on fish Evidence of fishing from the breeding grounds can be seen at the beaches, where fishermen dock with big catches of juvenile fish. Observers note that some of the fish caught also seem to be shrinking, indications of overfishing and poor water quality. “Some 15 years ago, fishermen used to come with huge fishes. I used to see Nile perch weighing up to 145 kilograms [320 pounds]. But the biggest I have seen this year was 69 kilograms [152 pounds],” said Okulo, the ecologist.

Grounded police patrol boats in Kisumu, Kenya. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The two boats, the MV Utumishi and MV Chui, lie idle by the lake. “For four years now, we have not been able to patrol the lake as required. And if we must do it, then we have to hire boats using our money which cannot be refunded by the government,” he said. The toll on fish Evidence of fishing from the breeding grounds can be seen at the beaches, where fishermen dock with big catches of juvenile fish. Observers note that some of the fish caught also seem to be shrinking, indications of overfishing and poor water quality. “Some 15 years ago, fishermen used to come with huge fishes. I used to see Nile perch weighing up to 145 kilograms [320 pounds]. But the biggest I have seen this year was 69 kilograms [152 pounds],” said Okulo, the ecologist.  A blessing or a disaster? Moris Okulo, an ecologist and lake guide, displays a Nile perch weighing 64 pounds. Carnivorous and fast-growing, Nile perch were introduced to Lake Victoria decades ago as a food source, but they quickly wiped out many native fish species. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. On a recent day, the biggest Nile perch caught weighed just 29 kilograms (64 pounds). The rest were much smaller, some weighing just a few grams. Even the Nile perch, which has been a key disruptor of Lake Victoria’s native ecology, is now at the mercy of hungry fishermen. In a presentation during a recent symposium in Entebbe, Uganda, Mbuthia pointed out that some of the fish samples his team collected for their study on estrogen levels in the lake had gross abnormalities, such as missing tails or fins, missing eyes, deformed bodies, or abnormal body color, which raises a new concern about the health of the fish in the lake.

A blessing or a disaster? Moris Okulo, an ecologist and lake guide, displays a Nile perch weighing 64 pounds. Carnivorous and fast-growing, Nile perch were introduced to Lake Victoria decades ago as a food source, but they quickly wiped out many native fish species. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. On a recent day, the biggest Nile perch caught weighed just 29 kilograms (64 pounds). The rest were much smaller, some weighing just a few grams. Even the Nile perch, which has been a key disruptor of Lake Victoria’s native ecology, is now at the mercy of hungry fishermen. In a presentation during a recent symposium in Entebbe, Uganda, Mbuthia pointed out that some of the fish samples his team collected for their study on estrogen levels in the lake had gross abnormalities, such as missing tails or fins, missing eyes, deformed bodies, or abnormal body color, which raises a new concern about the health of the fish in the lake.  Fishing boats rest on the shore of Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Ojijo, the maritime police officer, said that many people have recently been arrested for poisoning fish with various chemicals before picking and selling the carcasses. Other fishermen use inappropriate fishing gear that ends up trapping all sizes of fish, including the very young ones essential for replenishing the fish stock. Some of them even opt for tiny-meshed mosquito nets, which have raised additional concerns about leaching insecticides into the water.

Fishing boats rest on the shore of Lake Victoria. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. Ojijo, the maritime police officer, said that many people have recently been arrested for poisoning fish with various chemicals before picking and selling the carcasses. Other fishermen use inappropriate fishing gear that ends up trapping all sizes of fish, including the very young ones essential for replenishing the fish stock. Some of them even opt for tiny-meshed mosquito nets, which have raised additional concerns about leaching insecticides into the water.  Fishermen on Lake Victoria use inappropriate fishing gear that indiscriminately captures even very young fish, as seen in this photo. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The ecological health of the lake is further compromised by the water hyacinth, an invasive plant that has densely colonized huge swathes of the lake, choking out native aquatic plants and limiting oxygen supplies in the water. The water hyacinth thrives because of the soil and nutrients that flush into the lake whenever it rains. “In many cases, the soil erosion happens because people have cut down trees, and more people are cultivating very close to the lakes and rivers, contrary to regulations to protect wetlands, rivers and lakes,” said Kiyingi, the Ugandan activist. In Kenya, for example, the law requires that land near river banks, lake shores, and sea shores be used sustainably and asserts that special measures to prevent soil erosion, siltation, and water pollution are necessary. And NEMA laws require that new structures be built at least 30 meters from the shore. However, Bridgit Akoth, who owns a food kiosk that extends right into the lake at Dunga beach, told mongabay.com that she need only part with a few shillings to bribe law enforcers to let her go on with her business. “Most of these laws just exist on paper. They are rarely put into force,” said Kiyingi. “And now we have a price to pay, a price of losing the biggest fresh water lake in Africa.” Citations:

Fishermen on Lake Victoria use inappropriate fishing gear that indiscriminately captures even very young fish, as seen in this photo. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu. The ecological health of the lake is further compromised by the water hyacinth, an invasive plant that has densely colonized huge swathes of the lake, choking out native aquatic plants and limiting oxygen supplies in the water. The water hyacinth thrives because of the soil and nutrients that flush into the lake whenever it rains. “In many cases, the soil erosion happens because people have cut down trees, and more people are cultivating very close to the lakes and rivers, contrary to regulations to protect wetlands, rivers and lakes,” said Kiyingi, the Ugandan activist. In Kenya, for example, the law requires that land near river banks, lake shores, and sea shores be used sustainably and asserts that special measures to prevent soil erosion, siltation, and water pollution are necessary. And NEMA laws require that new structures be built at least 30 meters from the shore. However, Bridgit Akoth, who owns a food kiosk that extends right into the lake at Dunga beach, told mongabay.com that she need only part with a few shillings to bribe law enforcers to let her go on with her business. “Most of these laws just exist on paper. They are rarely put into force,” said Kiyingi. “And now we have a price to pay, a price of losing the biggest fresh water lake in Africa.” Citations:  A woman prepares fish at busy Dunga Beach. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu.

A woman prepares fish at busy Dunga Beach. Photo credit: Isaiah Esipisu.